Randy Johnson was unearthed in a gold mining town

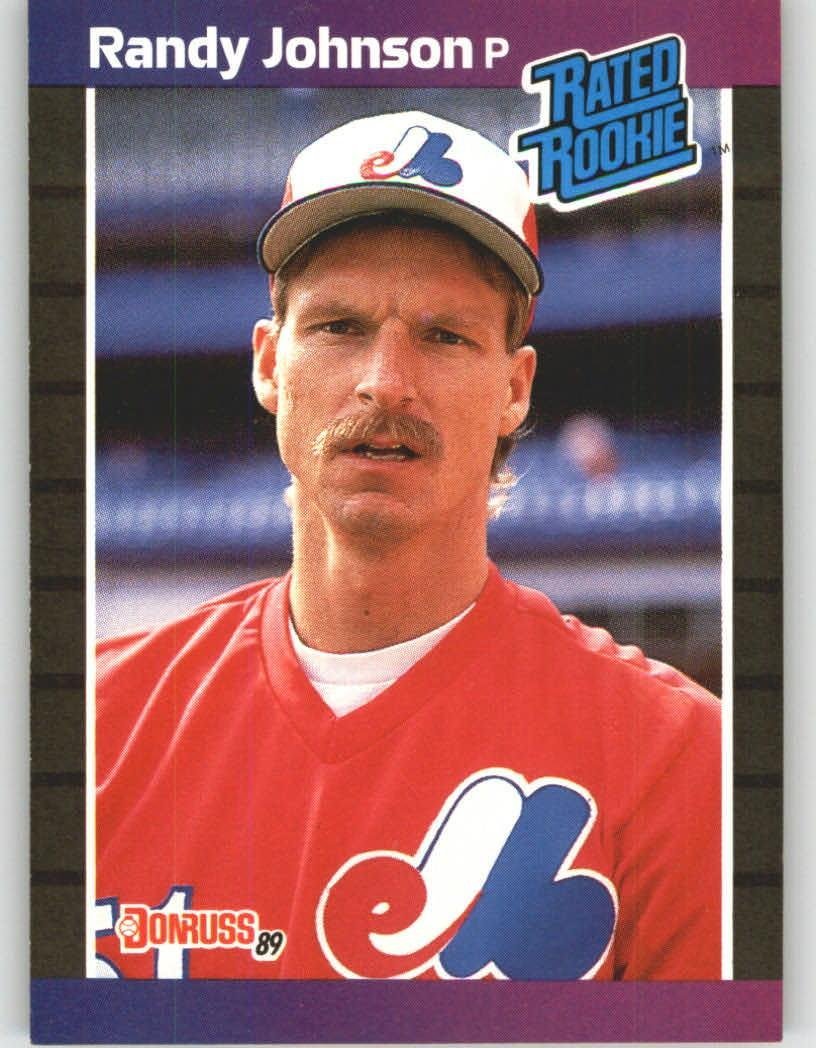

LHP Randy Johnson earned big-time status from Don Russ baseball cards in 1989 Sunday is inducted into the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

By: Danny Gallagher

When Bob Fontaine Jr. and Tom Hinkle drove into idyllic Grass Valley in northern California on a June day in 1985, they found themselves in an historic gold mining town in the Western Foothills of Sierra Nevada.

They were there for a specific reason. Knocking on the door of a house in the municipality, which dates to the California Gold Rush of the late 1800s, the two Expos’ scouts, with much trepidation, found themselves face to face with a pitcher they had been scouting for several years on a regular basis. Someone very tall, 6-foot-10, that is, very intimidating.

Little did they know that young man would become an inductee into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. 30 years later. That man was Randy Johnson. He gets inducted July 26 along with Pedro Martinez, another former Expos’ pitcher, Astros sparkplug Craig Biggio and Braves pitching sensation John Smoltz.

Not long prior to that visit to Grass Valley, the Expos had selected Johnson in the second round of the draft out of the L.A.-based University of Southern California which he decided to attend after rejecting a reported offer of $50,000 to sign with the Atlanta Braves, who took him in the first round in 1982 out of Livermore high school.

Johnson was born in Walnut Creek near Livermore but he and his parents relocated at some point to Grass Valley more than two and a half hours to the north. His father Bud was a policeman and also a security guard at Lawrence Livermore Labs and his mother Carol did odd jobs while raising Randy and five other siblings.

For many decades like in the 1980s, players did their own negotiating, not like today when high-powered agents spar with front-office personnel, most notably the general manager, president and maybe even the team owner. Back in the days when Johnson was drafted, players received five-figure or six-figure signing bonuses. For many years, though, the bonus has been in the millions. That’s why players have left the contract talks in the hands of agents.

“I do remember the visit to Randy at his parents’ house but it’s been quite some time,’’ Fontaine said in an exclusive interview after this reporter spent months and months off and on trying to track him down to talk on the phone. Fontaine left the Blue Jays earlier this year after a six-year run to join the Major League Baseball Scouting Bureau.

“Back in those days, scouts did the signing of players,’’ Fontaine said. “In negotiations, Randy was tough, he was fair. Players negotiate like they play: tough but fair. He was very, very active in negotiating his contract. He was very involved in negotiations along with his parents. He got a very fair signing bonus. The Johnsons were wonderful people.’’

Although the late Cliff Ditto, a brother-in-law of Duke Snider, didn’t join Fontaine and Hinkle at the negotiating table that day in Grass Valley because he was signing players in southern California, he was instrumental in watching Johnson umpteen times along the way.

“Tom, Cliff and I handled the scouting for the Expos in southern California,’’ said Fontaine, the 60-ish son of the late Bob Fontaine Sr., who spent decades as an executive and scout with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Pirates and Padres. “Cliff and Tom saw him a lot. In Randy’s junior year at USC, either one of us always saw him every time he pitched.

“Randy, like so many power pitchers and power hitters, developed one step at a time, from high school to college. We knew him from high school on. The biggest thing I noticed earlier on about him was that he was what we would call a thrower. Then he became a pitcher. When he started in college, he began to develop more extension with a a devastating breaking ball. With arm extension, when you’re a power pitcher or a power hitter, it takes longer to get consistency when you are a bigger kid. It takes time to get a consistent release.’’

Johnson only got his feet barely wet with the Expos before moving on to a stellar career in the uniforms of other teams but the Expos’ tenure was quite memorable for the late Jim Fanning, who was involved in scouting with the Expos at the time Johnson was drafted.

“Bob Fontaine’s father was a scout for years and years,’’ Fanning said. “I had Bob Jr. and Cliff go specifically to look at Randy. Rarely did I move them out of southern California.’’

So Fontaine and Hinkle finally got Johnson to sign with the Expos’ organization, although it wasn’t easy. He didn’t want to sign to play in the outpost of Jamestown, N.Y., which 10 years or so earlier met with much disdain from another California native and Expos great Gary Carter, who snickered/asked, “This is professional baseball?’’

“Randy didn’t want to sign a Jamestown contract,’’ Fanning said. “He thought he was much better going to Double-A or Triple-A. He may have been right. He did not perform for us early at Jamestown, I brought him in to Montreal before a major-league game late in the afternoon. It was just a workout. Randy wouldn’t throw the ball for us. He would throw hard but he wouldn’t bare down like he should have.’’

So in no uncertain terms, Fanning went over to Johnson and gave him a scolding, saying, “Randy, you gotta throw harder than that. You never threw the ball.’’

As Fanning would reveal in the conversation with me, “I’ve never ever told anyone about my lecture to Randy Johnson on the pitching mound in the bullpen in Montreal.’’

Several days later in Jamestown after Fanning’s sermon, Johnson threw harder in a performance that left Fanning fawning.

“He was absolutely dominate. Absolutely,’’ Fanning said in the last interview he gave 10 days before he died April 25. “Randy said, ‘I’m going to go down there and show these guys what I can do.’ He showed it all. He showed big-league stuff. This guy is for the big leagues. You had to like him for his arm delivery.’’

Following his apprenticeship in Jamestown, Johnson would make minor-league stops for the Expos in the Florida venues of West Palm Beach and Jacksonville and then Indianapolis. With the Jax Expos, Johnson was 11-8 on a team that included Brian Holman, Larry Walker, Nelson Santovenia and Rangers castoff George Wright, who was trying to rebuild his career.

Holman, for one, is very close to Randy Johnson? How close?

Let’s put it this way: Holman is making his way from his home in Olathe, Kansas to Cooperstown to see his friend being inducted July 26. How is that for closeness?

“Randy is a true friend. We played together in the Expos’ minor-league system, we played together with the Expos and we got traded together to Seattle,’’ Holman said.

“Randy was a tall, lanky, slim kid, who always had trouble putting weight on,’’ recalled Santovenia, a teammate of Johnson with Jacksonville, Indianapolis and then Montreal. “He threw hard. He had control issues. He’d load up the bases and come back and strike out the side.’’

It was during his time in Jacksonville that a mini brawl erupted during one game and Johnson would settle things down by throwing 97 m.ph. heat to calm the opposing team down.

“That was Randy’s way of saying, ‘Don’t mess with the family.’ He took care of the family,’’ recalled Tommy Thompson, Johnson’s manager in Jacksonville. “It was not I. It was we. It was something we taught. I told him to not let umpires or the opposition get to him. e gotHe got better and better.’’

If Holman had to think of an anecdote about Johnson, it was June 15, 1988 in Indianapolis when Johnson’s pitching hand was hit by a line drive.

“He walked off the mound, headed to the dugout and took his right hand and smashed it against a helmet/bat rack in disgust,’’ Holman said.

When Expos minor-league pitching coordinator Joe Kerrigan heard about the incident, he would say, “Good thing it wasn’t his pitching hand.’’ Results from the line drive turned out negative and the front office was steamed at Johnson.

Whenever Johnson would show up in Montreal in between options to Indianapolis, veteran Expos pitcher Dennis Martinez would see things unfolding.

“What he was going through, I tried to help him. He had the talent but he was so wild. He was trying to do something with it,’’ Martinez said on the phone from Miami. “He had the size and he had the power in his arm, something you don’t see very often.

“He was frustrated, not being able to succeed in throwing a strike. He needed to have perseverance in going through the process in adjusting to his body. He was still getting uglier,too,’’ Martinez said, laughing. “Every aspect of his life was changing. He was still growing.’’

By the spring of 1989, the Expos appeared they had the impetus for a playoff spot but GM Dave Dombrowski was still looking for a veteran starting pitcher and the binoculars focused on Mariners lefty Mark Langston. The trade came down in May, 1989: Johnson, Holman and reliever Gene Harris to the Mariners for Langston.

“Dave Dombrowski was on the phone with me a lot before that trade,’’ Fanning said. “I told Dave that if acquiring this guy would win the pennant for us, you have to do it. It was giving away the farm. It was a hard deal for me to give Johnson up. Holman and Harris were also guys who were making contributions to the organization. No question it was a bad deal.’’

That’s for sure. The Expos faded during August and early September and fell out of the race, an embarrassment that so angered majority owner Charles Bronfman that he unloaded the franchise. Of course, Langston turned down free-agent overtures from the Expos in the off-season and signed with the Angels.

“The guy we didn’t want to give up in that trade was Harris,’’ recalled Gary Hughes, the Expos’ scouting director in those days.

In the end, Johnson pitched until 2009, Holman was out of the game following the 1991 season due to shoulder problems and Harris never pitched in the bigs after 1995.

Johnson is the subject of a just released MLB Network documentary called The Big Picture: From Raw Talent to Dominant Force. The raw talent, of course, was exhibited in his Montreal days. The video is narrated by Mettalica band lead singer James Hetfield.

Anyone associated with the Expos would be proud of Johnson. There will be busloads of Expos’ fans coming from Montreal, Ottawa and other venues to see him being inducted. One would think Johnson will make time in his speech to chat a little about his Expos’ days and maybe mention a few people, who helped him along the way, like Kerrigan and Rick Williams, an Expos’ organizational pitching instructor, among others.

As Fontaine looks back to 1985 and looks ahead to Johnson’s induction, he can’t help but be proud of the fact that Johnson is Cooperstown-bound.

“It’s a thrill,’’ Fontaine said.

Fontaine chuckled almost sheepishly when he told me he began scouting in 1973 at the very young age of 19. One would bet Johnson is his most prized signing and most prized player he brought into any organization. Fontaine was 28 at the time.

“It doesn’t happen very often,’’ Fontaine said of seeing someone he scouted and signed go to Cooperstown. “I was associated with him. I was a big part of him, scouting him and signing him.’’

Danny Gallagher will be on hand in Cooperstown for the induction ceremonies. On July 25, he is signing copies of the 1994 Expos’ book he co-authored with Bill Young called Ecstasy to Agony. The session takes place from 2-6:30 at Willis Monie Books on Main St., just down the street from the Hall of Fame.