Expos were bound for L.A. during the Rodney King riots

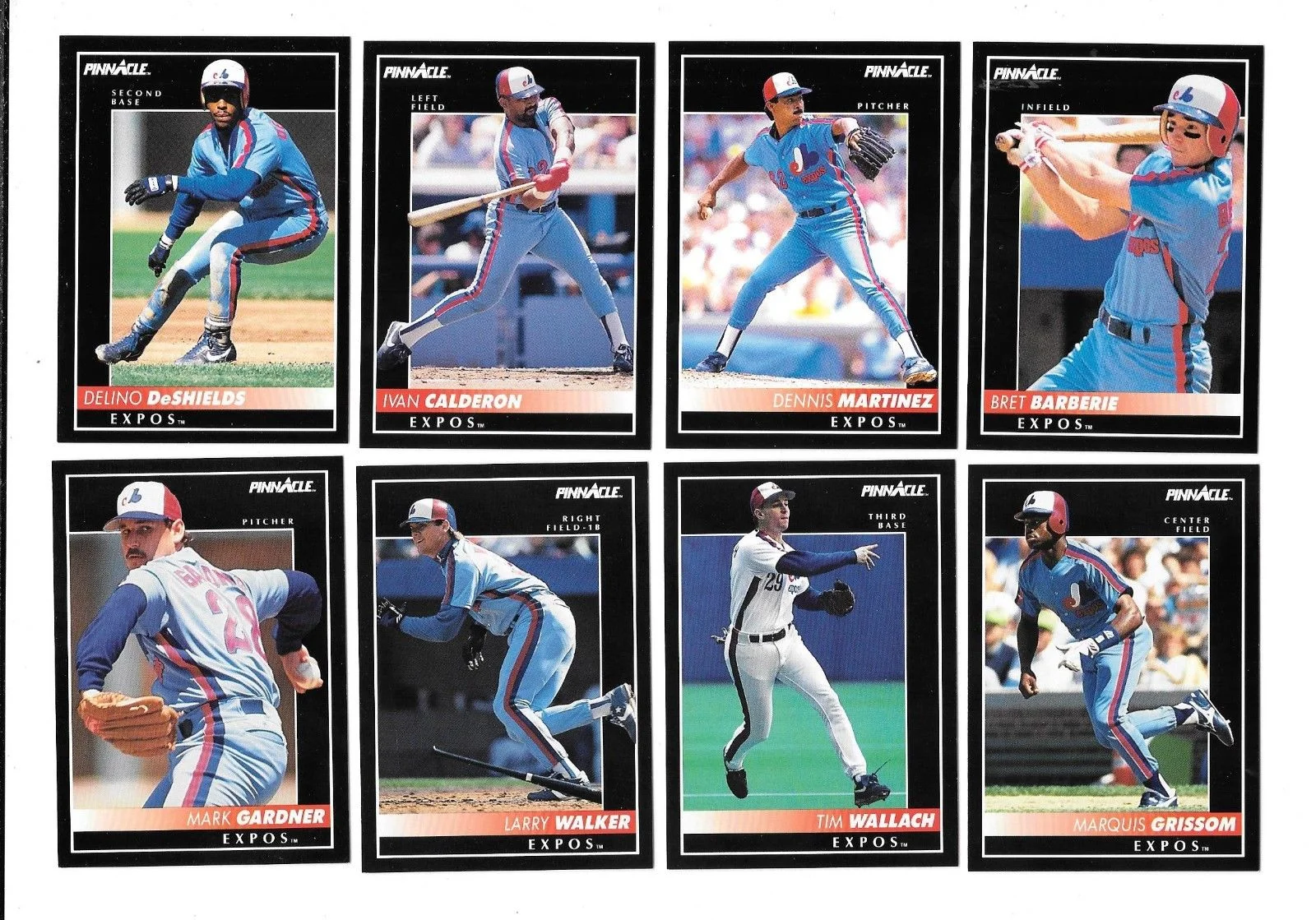

These are eight of the Montreal Expos that were part of the club that was scheduled to play the Los Angeles Dodgers in a three-game series at Dodger Stadium in April 1992 when the Rodney King riots broke out. The series was postponed until July.

By Bill Young

Canadian Baseball Network

Portions of this story first appeared in Ecstasy to Agony: the Montreal Expos – How the best team in baseball ended up in Washington ten years later... by Danny Gallagher and Bill Young

It’s been 25 years since the city of Los Angles was ravaged by what became known as the Rodney King riots. Ignited on Wednesday night, April 29, 1992, this epic rampage followed directly upon the heels of the jury acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers who had been charged with excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King on March 14, 1991. Most of it had been caught on videotape.

The verdict stood out as an egregious flaunting of police authority and the law, especially with haunting images of the violent beating flashing across the television screens of the nation almost every night since it had occurred.

In the eyes of the African-American community, indeed of much of America, the four police officers were guilty and deserved to be punished for their ugly deeds. That they were not was deemed to be the last straw. It was time to take to the streets.

Rioting spread like wildfire across the city that Wednesday night as the masses, looters, arsonists and mischief makers committed virtually every act of civil disobedience in the book. The situation became so out of control, the city was placed in lockdown.

***

While all this was going on, the Montreal Expos were preparing to fly from San Diego into Los Angeles to play a three-game series against the Dodgers at Chavez Ravine – just another in a string of bad luck that had dogged the club ever since owner Charles Bronfman decided in late 1989 to step aside, and designate Claude Brochu to be his successor.

From that point to this, air had been slowly leaking out of the Expos balloon, with team morale spinning from bad to worse. By now, with the team caught up in the L.A. mayhem, spirits were plummeting to an all-time low, and it showed, both on the field and off.

The 1990 trading of future Hall of Famer Tim Raines (St. Marys and Cooperstown) to the White Sox had set the tone, but it was the 1991 season that really did our Expos in. Finishing in last place with a 71-90 record, 26-1/2 games out in their division, the team had put together its worst performance since 1972.

But there was more: in mid-season general manager Dave Dombrowski chose to replace veteran manager Buck Rodgers with the untested Tom Runnells, a young man who clearly was not up to the task facing him. Then, even before the season ended, Dombrowski, ever scouting out greener pastures, himself packed up and moved to Florida where the future Marlins were beginning to take their first baby steps.

Why, even Olympic Stadium - the Big O or Big Owe, take your pick - seemed ready to give up the ghost. After a summer series of minor setbacks, e.g. the roof ripping during a rainstorm dousing the paying customers, dangerous objects periodically dropping from the roof, and so on, the stadium suffered what would have been a truly major catastrophe had it occurred on a game day.

On Friday, September 13, and completely without warning, a huge 55-ton concrete slab separated from one flank of the building and crashed down an outside walkway near a cluster of ticket booths. Fortunately, the Expos were on the road and there were no serious injuries.

Had the schedule been slightly different, had the team been enjoying a home stand, what with folks lined up early to purchase tickets and so on, the result would have been tragic.

Even so, the blow to the team was dispiriting enough. With 13 games left in the schedule, and no way to repair the damage to Olympic Stadium before season’s end, all remaining games, even home games, would have to be played on the road.

By the time the dust settled and the nightmare ended, the club’s final numbers indicated that not only did Montreal finish last in the division, but for the first time since 1976 total attendance numbers dropped below seven figures.

The season, however, was not without its golden moments, with the perfect game Dennis Martinez tossed on July 28 in Chavez Ravine against the Dodgers leading the way. Twenty-seven up; twenty-seven down. Broadcaster Dave Van Horne’s excited call the moment the final out was recorded still echoes in the hearts of Expos’ faithful.

“El Presidente...El Perfecto”.

Sadly, this remarkable accomplishment was not a harbinger of things to come. Not at all.

***

Not surprisingly the 1992 season started much like the ’91 campaign had ended - under a protracted shadow of gloom. Although manager Tom Runnells attempted to introduce an aura of authority during spring training, he failed. Players and media alike, and even the fans, were already well aware just how much he lacked the wherewithal to back it up.

When in a misguided, self-deprecating gesture he thought might relieve tension and lighten the atmosphere in camp, Runnells rolled out onto the training grounds in a military vehicle, dressed in army fatigues. Instead it came to represent the moment when he lost all credibility.

To make matters worse Runnells then decided that to shore up his infield he would move veteran third baseman Tim Wallach to first base and install the untested Bret Barberie at third.

Wallach acquiesced, albeit reluctantly, but the questionable logic behind Runnells’ decision quickly became a focus of dissent. Constant rumblings from the clubhouse confirmed Runnells was not up to the task of managing major league players: his style might have worked in the minors but was abhorrent in the big leagues.

***

And so that April night as Nos Amours were flying into Los Angeles at the tail end of a 10-game road trip having already lost five of seven, being caught up in the Rodney King-inspired riots just seemed par for the course. One can only imagine the ominous concern that gripped players as bit by bit they began to fully absorb news of the violence and acts of destruction washing across the city.

Los Angeles Times scribe Scott Miller wrote: “minutes after their 9-3 victory Thursday over the Padres… the Montreal Expos dressed with one eye on their socks and the other on pictures from Los Angeles,” adding, “Subdued, withdrawn and nervous, they are due in Los Angeles today for a weekend series with the Dodgers, and they do not want to go.”[ii]

The riots had begun toward evening on Wednesday night, shortly before their arrival. Vin Scully had called the Dodgers-Phillies game that night from his booth at Chavez Ravine, even as the city was beginning to boil over with rage. As live images from the streets played across television sets in his booth, Scully knew he had to remain calm. He later wrote he “was extremely aware of the obligation I had not only to broadcast the game, but my obligation to maintain the safety of…people at the ballpark or panic. So I said nothing. It was very painful.”[iii]

When it became obvious that no baseball could be played for the next few days there was some talk about shifting the series to Montreal, or even moving it to Anaheim Stadium. However, neither option proved practical.

"A lot of us feel like the games won't take place," Tom Foley, Expos’ player representative said at the time. "By looking at the TV shots they're sending out all over the world, how can you say, 'Everything is fine now; you go play the game?'”

In the end the Dodgers solved the dilemma for everyone: they postponed games for four days straight, including the Expos weekend series. Larry Walker spoke for his teammates when he said that given the option, “I'd rather go back to my own beautiful country.”[iv]

And so they did, a relieved group of ballplayers, already preparing for a return engagement against the same three West Coast teams the next week at Olympic Stadium. This time Nos Amours took five of the eight games played.

The impact of the riots on the Dodgers, both as a team and individually, was visceral and personal. Manager Tommy Lasorda spoke for his club once the team finally made it back onto the field in Philadelphia, after almost a week of inactivity: “Everybody knows that what happened was bigger than our game,” he pointed out. “It put a tremendous scar on our entire city."[v]

Certain players were touched by these events in very immediate and sometimes contradictory ways. Writing in the New York Times shortly after the riots wound down, Claire Smith mentioned Darryl Strawberry as a case in point. On the one hand, wrote Smith, “He greatly sympathizes with the youths who have come up behind him in South-Central, their lives more greatly affected than his was by the gangs, by the overabundance of weaponry, by the sheer fear of stepping from one's home.”

However, Smith pointedly added, Strawberry's older brother, Michael, was an officer with the Los Angeles Police Department and while on patrol, “Michael Strawberry was wounded in South-Central last Friday when his patrol car was strafed by fire from an AK-47 assault rifle….He was grazed by a bullet and flying glass.”[vi] How can anyone make rational sense of such a conundrum?"

Perhaps teammate Eric Davis, himself an escapee from the mean streets of L.A., had the firmest grasp on these conflicted emotions. “It makes you put life into perspective," he told Smith, "You have to concentrate on the game; we owe that to the Dodgers. But the fact is that our minds are still going to be there. It hit home. It's reality, especially for the people who grew up there."[vii]

It was simpler for the Expos. Life went on and the team’s fortunes improved. The three dates postponed in early May were eventually rescheduled in July when Montreal returned to Los Angeles for a regularly scheduled three game series, except now they would have to play six games and in just three days: three twin-bills in a row.

The Expos lost both ends of the first encounter, swept the Dodgers in the second, and the clubs split the finale.

When the dust settled the Expos’ record stood at 42-42. They would not drop below .500 for the remainder of the season.

Of course, by this time Tom Runnels had been given his walking papers and a new manager introduced into the mix. Felipe Alou. After all these years Mr. Alou had finally been granted his first opportunity to manage a major league club.

He did not disappoint.

***

[ii]Scott Miller, “Expos Forced to Wait as L.A. Violence Grows,” Los Angeles Times, May 01, 1992

[iii] Smith, Curt Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc. 2010) p.183

[iv] Miller,

[v] Claire Smith, “Baseball; Dodgers Are Trying to Put Turmoil Behind Them”, New York Times, May 6, 1992.

[vi] Smith,

[vii] Smith,