Glew: My ode to Chet Lemon

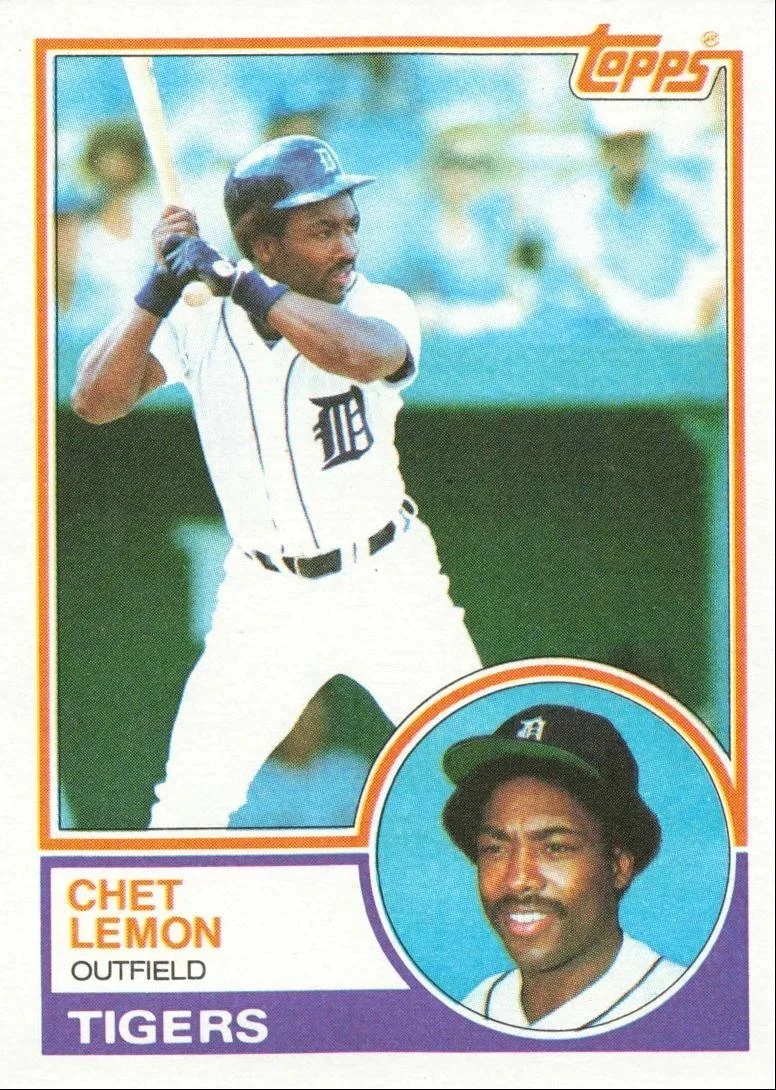

Chet Lemon was an underrated centre fielder for the Detroit Tigers for many years.

June 18, 2025

By Kevin Glew

Canadian Baseball Network

It was after I’d airmailed yet another ball over our first baseman’s head during infield practice at second base that my coach, Lorne Thompson, had finally seen enough.

Never one to sugarcoat, he told me he was moving me to the outfield before I killed someone.

I was only 13, but I knew it was the right decision.

I was clearly no Lou Whitaker.

Coach T was also aware that I loved to shag fly balls during batting practice.

“Let’s try you in centre field,” he said.

And with that, a love affair was born.

At that age, I felt uncertain about almost everything, but I knew I loved to chase fly balls.

And thanks to my coach and my dad hitting me countless tennis balls down Thames Crescent, the street I grew up on in Dorchester, Ont., I got plenty of reps.

“Will you hit me some?” I would plead to my dad after supper almost every night, from spring through fall.

And, regardless of all the things he had to do, my dad usually obliged.

And so my career as a centre fielder began.

I received tips from my coach and my dad, but I mostly taught myself through endless practice. There was little grace or precision to my pursuit of a fly ball, just sheer, reckless passion.

A cautious and anxious kid, I found myself transforming into a maniac when tracking a fly ball.

When my dad hit me tennis balls down the street, I would leap fearlessly into my neighbor’s pine trees, often emerging with cuts and scratches, and sometimes even the ball.

I did this so often that I can remember pine needles falling out of my clothes when I changed at night.

At team practices, I’d dive on the edge of the gravel infield at our home diamond in Dorchester. Sometimes I didn’t catch the ball, but I’d almost always rip a hole in the knees of my pants. Just ask my mom.

I really couldn’t explain my intensity. For a kid who was generally reserved and polite, for some reason, I’d lose my inhibitions when chasing that nine-inch white sphere in the sky.

Our home field in Dorchester didn’t have an outfield fence, which actually helped me improve as a centre fielder. I had to learn how to run back – way, way back. Sometimes I even had to traverse a live soccer game on the field behind us to retrieve a ball.

In 1986, the year I made my position switch, I was a Toronto Blue Jays fan. I loved Lloyd Moseby, their left-handed hitting centre fielder, but I was a right-handed hitter with far less pop, charisma and confidence than the man known as “Shaker.”

Somehow, despite only occasional glimpses of him on This Week in Baseball, Dale Murphy, the Atlanta Braves star centre fielder, was my favourite player.

Like me, Murphy batted right-handed, and I spent countless hours mimicking his stance in the reflection in the big window in the back of my parents’ garage. But though I had his stance down pat, I could never match his power or his five-tool skill set. And I realized very quickly that though I loved Dale Murphy, I was never going to be Dale Murphy.

No, I found the centre fielder I’d model my game after while manually changing the channels on my parents’ behemoth RCA TV in their basement. Growing up in Southwestern Ontario, we were fortunate to have WDIV Channel 4 Detroit as part of our cable package and they would regularly broadcast Detroit Tigers games.

Even today, when I close my eyes, I can hear George Kell calling an Alan Trammell home run, a Kirk Gibson double off the wall or most exciting for me, a diving play by Chet Lemon.

By 1986, I had learned that like me, Lemon was a right-handed hitting infielder who had been converted into a centre fielder. And like me, he had to employ everything in his tool kit to get on base. He’d bunt, sprint out an infield single and was more likely to double than homer.

And like me, he always looked a little unnatural and off-balance in the batter’s box.

Sure, he was infinitely more talented than me, but I could relate to him.

When I ran back for a ball on our fenceless home diamond in Dorchester, I felt like Lemon patrolling the cavernous centre field (440 feet to the wall) at Tiger Stadium.

And like Lemon, I chased fly balls like I was possessed, with a manic energy, with more guile than grace. Lemon would crash fearlessly into a wall at Tiger Stadium the same way I’d leap recklessly into my neighbor’s pine trees on Thames Crescent or bloody myself diving into the edge of our gravel infield in Dorchester.

So, this is why when it was announced that Lemon had died at age 70 on May 8, it hit me particularly hard.

I never met Lemon, but it feels like he was “there” for me when I was navigating that awkward transition from child to teen, from hapless, anxious infielder to fearless, more confident centre fielder.

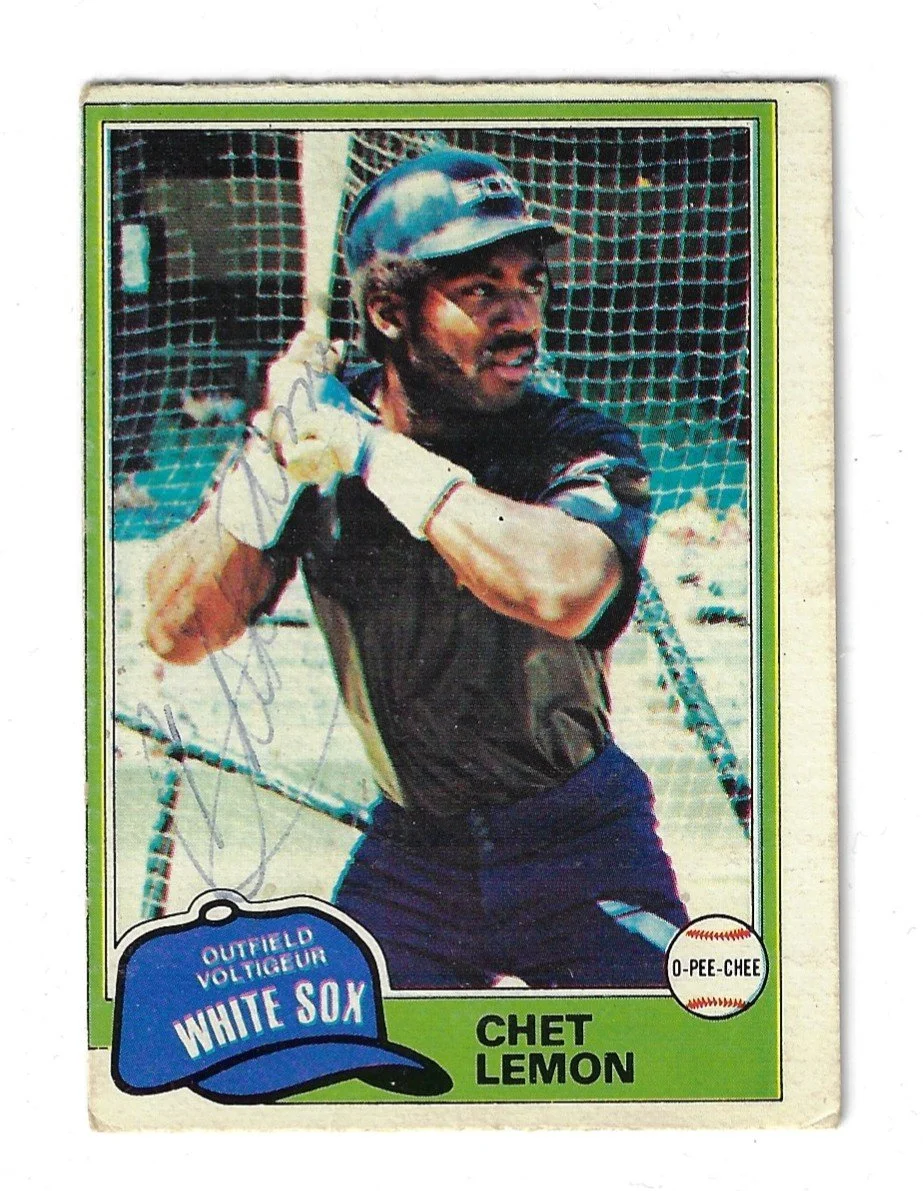

When I was 13, I wrote Lemon a letter and sent it to Tiger Stadium. I told him about my position change, about how much he inspired me and that I was channeling him in centre field in Dorchester, Ont. I included a 1981 O-Pee-Chee card and asked him to sign it. So, I was elated when one day I came from school and there was an envelope with a Detroit postmark on it. Lemon had signed and returned my card.

The 1981 O-Pee-Chee card Kevin Glew mailed to Chet Lemon at Tiger Stadium in 1985.

When Lemon’s death was announced, I went to my parents’ place and found that card.

During that search, I was surprised to discover that there was still such a big place in my cynical, middle-aged heart for the hustling, underrated Tigers outfielder that I had channeled nearly 40 years earlier.

Lemon’s death wasn’t totally unexpected. In recent years, his body had been ravaged by multiple strokes and blood clots that confined him to a wheelchair, unable to speak.

Last fall, in his final public appearance, Lemon returned to Detroit for the 40th anniversary of the 1984 World Series-winning Tigers team.

Videos show him interacting with his teammates. There’s some especially moving footage of him hugging Trammell, who played shortstop in front of him for so many years.

I like to think that in Lemon’s mind that weekend, he was coming to play centre field in Detroit one last time.

I vividly remember that dominant 1984 Tigers squad. They started the season 35-5 and Lemon was a big reason for their success. He had 20 home runs and was named an All-Star. And, if you asked me right now, I could re-enact his tremendous, twisting and backpedaling catch in centre field in the seventh inning of Game 3 of the World Series.

As a teen, I continued to channel Lemon in centre field over the next several years. I even forgave him when he and his Tigers broke my young Blue Jays-loving heart in the last week of the 1987 regular season.

Lemon’s production tailed off after that season and he retired following the 1990 campaign.

After his playing career, Lemon fought through a blood disorder to start his own baseball school in Lake Mary, Fla. From that school sprouted an elite trailblazing travelling team called Chet Lemon’s Juice. Zack Greinke and Prince Fielder were among the graduates.

From the videos I’ve seen, even near the end, despite having endured multiple strokes, blood clots and hospitalizations, Lemon never appeared to lose his zest for life. I admired him for that and thought to myself that I should be more like him. It was similar to how I felt in centre field four decades earlier.

So, when Chet Lemon died, it hurt.

Like I said, I never met him but he helped me navigate centre field and life. He and Coach T helped instill confidence in me at a crucial, formative age. And most importantly, without aspiring to be him, I wouldn’t have spent all of those evenings with my dad on Thames Crescent.

For that, Chester Earl Lemon, I say thank you.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I think I’ll go ask my dad to “hit me some.”