Kennedy: Why doesn’t Tommy John have a plaque in Cooperstown?

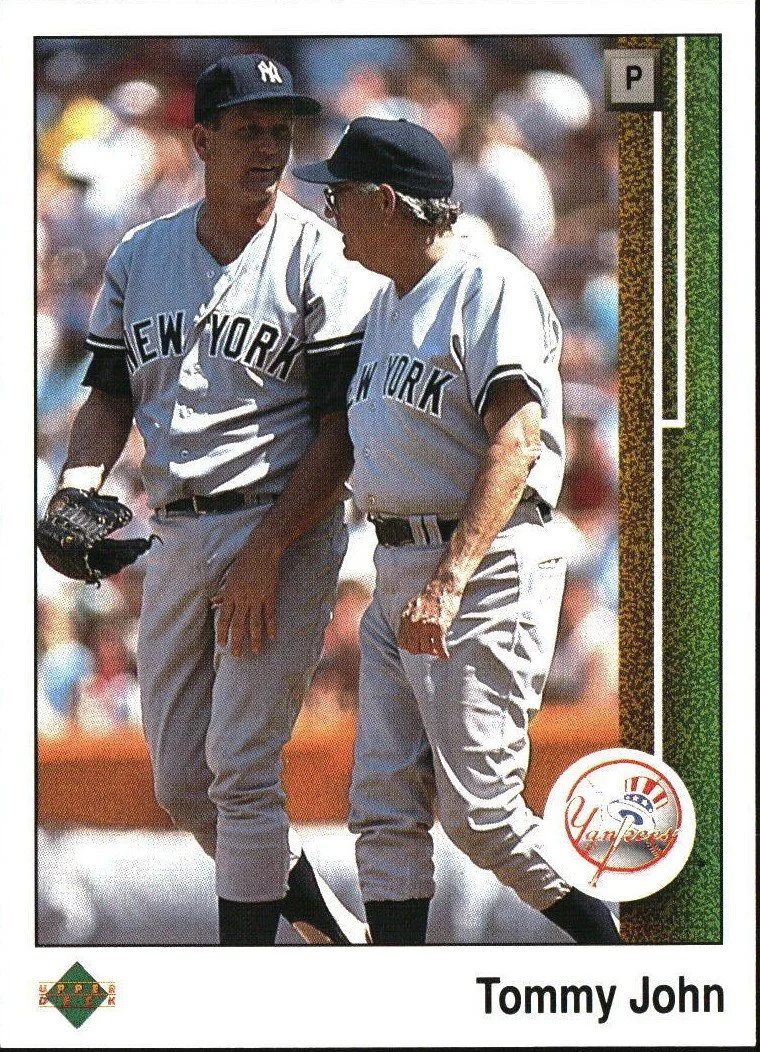

He recorded 288 wins and was the first to undergo a revolutionary surgery that bears his name, so why hasn’t Tommy John (pictured above) been elected to Cooperstown?

May 24, 2025

By Patrick Kennedy

Canadian Baseball Network

"When they operated on my arm, I asked them to put in a Koufax fastball. They did, but it turned out to be Mrs. Koufax."

- former major-league pitcher Tommy John.

What springs to mind when you hear the name “Tommy John”?

If you answered “underwear,” well... you're right, but you can stop reading here.

This is a baseball column, and baseball and skivvies are seldom mentioned in the same breath unless it's a superstitious player explaining how he sports the same pair of gotch during a hitting streak. (Let's hope – at least for his teammates sake – that Joltin' Joe DiMaggio wasn't the superstitious type during his record-setting 56-game streak.)

If when you hear the name “Tommy John” you think of “ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction surgery,” medically speaking you know your apples, as the saying goes.

If you said “former major league pitcher,” first prize is yours.

Indeed, before the underwear maker (no relation) and before the elbow ligament-replacement surgery which became known as “Tommy John surgery,” there was Tommy John the major league pitcher and pioneer patient in the revolutionary procedure that has prolonged the careers of hundreds of pitchers. Today, fully a third of MLB pitchers have undergone Tommy John surgery.

John, known to teammates back in the day as “TJ,” was a durable, deceptive starting pitcher. In today's salary-bloated era, you'd need a Brinks truck to deliver his pay. The crafty southpaw pitched for 26 big-league seasons (1963-1989). That's the second most ever next to Nolan Ryan's 27 campaigns. His career arc spanned the administration of seven U.S. presidents, from Kennedy to Reagan. A four-time all-star, he posted a career won-loss record of 288-231 (3.34 ERA )and pitched in three World Series, each time for the losing side. He played for six teams and was his club's Opening Day starter on six occasions.

Such longevity in the sport isn't only rare, it's downright remarkable considering that 13 years into John's big-league career, in July 1974, the then-31-year-old Los Angeles Dodger sustained what seemed like a career-ending injury. He tore the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in his money arm. Ligaments are bands of tissue that hold bones together and help control the movement of joints. The UCL is located on the inside of your elbow. Without getting too deeply into the anatomy of it, let's just say that if you injure it, you'll have a tough time throwing a baseball to anyone, let alone a big-league batter.

When John tore his UCL, it ended a splendid season. He was 13-3 at the time and in the conversation for the National League Cy Young Award.

Two months later, Dodgers orthopedic surgeon Dr. Frank Jobe performed what was then experimental surgery. He removed John's damaged ligament and replaced it with a tendon from his right wrist. It marked the first time the procedure had been done on a baseball pitcher. Jobe didn't mince words on the possible outcome. He told his patient there was “one-in-a-100 chance” of success.

“That was better than zero in a hundred,” John recalled the other day on the phone from his Florida home. “I remember saying 'Doc, you do your job, I promise I'll do the rehab.' I was determined to pitch again.”

He did. Better than ever before.

Following a so-so 10-10 record in 1976, his first year back from his surgery, John posted his first 20-win season, going 20–7 with a 2.78 ERA for the 1977 World Series-bound Dodgers. He helped the club return to the Fall Classic in 1978 before signing with the New York Yankees as a free agent. In the Bronx, he posted back-to-back 20-win seasons (1979-80) and earned All-Star kudos each year. After stints with the California Angels and Oakland Athletics, he returned to an injury-plagued Yankees’ rotation in 1987, winning 13 games at the tender age of 44.

John's 288 wins are the seventh most in MLB history by a left-handed pitcher; the six ahead of him all are in the Hall of Fame. What's more, his victory total stands 25th on the all-time career wins list. Every pitcher above him, with the exception of PEDS-tainted Roger Clemens, is in the Hall of Fame.

So why isn't TJ enshrined at Cooperstown?

Good question, especially in light of the fact that those 288 wins are more than the win totals of a host of Hall of Famers, including Jim Palmer, Dizzy Dean, Bob Feller, Fergie Jenkins (Chatham, Ont.), Jim Kaat, Jack Morris, Roy Halladay, Robin Roberts, and several others. Incidentally, John bested childhood hero Robin Roberts to earn the first of those 288 wins, tossing a complete-game, 72-pitch jewel that was over in one hour, 34 minutes.

“I never needed a pitch-clock,” he said, chuckling.

In the modern era of Major League Baseball, only one “clean pitcher” with more than 270 wins is on the outside looking in at the Hall of Fame. His name is Thomas Edward John Jr., a lineman's athletic son from Terre Haute, Ind., who as a teenage basketball player was recruited by more than 50 U.S. colleges and universities. And here's the kicker: John compiled a major-league best 188 no-decisions.

“Right there that tells you something,” he pointed out. “If just a quarter of those no-decisions go my way, it puts me well over 300 wins.”

As with hitting 500 home runs, 300 pitching wins all but guarantees Hall of Fame induction, save for those stained by steroid accusations.

“I believe I deserve to be in the Hall of Fame,” John said unequivocally.

Incredibly, he never topped 40 percent of the 75 percent needed for selection.

“Hey, at this stage, if it's meant to be, fine. If not, so be it.

“When my friend Jimmy Kaat got elected (2022), he phoned and apologized, saying: 'TJ, you should be in there before me.' I said, 'That's OK, Kitty. If it happens, it happens.”

Tommy John recently turned 82.

Though his fame is tied to one particular surgery, John, who turned 82 this month, has also endured operations on his knees and hips. He's also had a number of health issues, including a life-threatening case of COVID. On the day we spoke, his second wife, Cheryl, had just brought him home after a five-week stay in hospital where he was treated for bladder cancer.

John has also experienced more than his share of family tragedies, none more painful than the 2010 death of son Taylor, the youngest of four John children. In 1981, his two-year-old son Travis fell out of a third-storey window and landed on the hood of a parked car. The child was placed in a medically-induced coma for 10 days. John, then with the Yankees, received an outpouring of support from around the U.S. including get-well wishes from President Ronald Reagan, former presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter, and crooner Frank Sinatra. Yankee teammate Reggie Jackson visited Travis in the hospital every day.

“Reggie sped up Travis' recovery, I have no doubt about that,” John said.

Jackson escorted Travis to the Yankee Stadium mound to throw out the ceremonial first pitch in a 1981 playoff game against the Milwaukee Brewers, while Travis's father finished his warmup tosses in the bullpen.

“They used a lighter rubber ball and drew red stitching on it so Trav could throw it farther,” John recalled.

Jackson called it “one of the biggest thrills of my life.”

“I can still hear 65,000 Yankee fans serenading Trav with chants of Tra-vis, Tra-vis, Tra-vis,” added John. “That moment will stay in my mind forever.”

Surprisingly, the sport at which he toiled for 26 big-league campaigns no longer draws his interest.

“I don't even watch it anymore,” he said. “It's not the same game. People who never played the game are running it using numbers and analytics and all that stuff. Too much BS...doesn't float my boat.”

What became of the arm cast he wore after undergoing sport's most famous surgery?

“It's in the Smithsonian (in Washington, D.C.),” he said.

And might that plaster of paris follow John to Cooperstown if/when he's ever inducted?

“You'll have to ask the Smithsonian,” he said with a laugh. “It's their cast now. I gave it to them.”

Patrick Kennedy is a retired Whig-Standard reporter. He can be reached at pjckennedy35@gmail.com