Mark Whicker: R. I. P. Frank Howard a Dodgers and Senators giant

Frank Howard, former National League Rookie of the Year

October 31, 2023

By Mark Whicker

Canadian Baseball Network

Sam McDowell was a fearsome lefthander for Cleveland. But he had his fears, too.

One was the sight of Frank Howard, the 6-foot-7 outfielder/first baseman who was baseball’s most feared volcano. Dormant for long stretches, Howard would belch smoke at the very sight of Sudden Sam.

So Cleveland manager Alvin Dark took action. When Howard came up to the plate for Washington, Dark moved McDowell to the outfield and brought in a reliever. It wasn’t much of a risk; if Howard did hit a fly ball, the odds were good it would fly into a neighboring street.

That’s Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle, left with Big Frank. Photo: Olen Collection/Diamond Images/Getty Images.

Then Dark moved McDowell back to the mound when the storm passed. These days, a large player isn’t unusual. In the 60s, Howard almost resembled a circus character. He weighed 255 pounds, and if a baseball had eyes, it would have closed them on the 60 foot, six inch journey to Howard.

Exit velocity was not a thing back then. Howard would have taxed the speedometer and the odometer. A 500-foot blast was part of his routine and, in Washington, they painted seats white if Howard’s home runs reached them. Players who followed noted those white seats, heard that a man had actually hit a ball there, and shook their heads.

Yet Howard was as gentlemanly and generous as anyone in the game. He saved his anger for himself, particularly with the Dodgers, where he had been Rookie of the Year but couldn’t meet all the Ruthian projections. In Washington he found playing time, and even though the Senators were rarely competitive, he gave people a reason to come to D.C. (later RFK) Stadium.

Washington lost the Senators to Texas, where the team became the Rangers and played Game 3 of the World Series Monday night, shortly after Howard passed away at the age of 87. The Montreal Expos eventually moved to the nation’s capital. Statues of Howard, Walter Johnson and Josh Gibson stand in front of Nationals Park today.

Howard hit 382 home runs with an OPS of .851 for his career, and finished in the top 10 of MVP voting four times. In 1968, the Year of the Pitcher, Howard slammed 44 home runs, eight more than anyone else in baseball. He also hit a league-leading 44 in 1970 and drove in a league-leading 126 runs, and also led the league with 132 walks. That was attributable to Senators manager Ted Williams, who loudly asked Howard, “How can a guy hit 44 home runs and walk only 54 times?”

Howard during one of his two stints coaching with the New York Yankees

Williams also said Howard was the strongest man he’d ever seen in baseball. All those numbers would attract some Hall of Fame support today. His career OPS-plus, measured against a league average of 100, was 142. Bryce Harper’s OPS-plus is 143. Vladimir Guerrero’s was 140. Duke Snider’s was 139.

In uniform, Howard dwarfed all past experiences. Snider was on third base one day and broadcaster Vin Scully remarked that Duke had better watch himself. On the next pitch Howard smoked Snider with a drive that briefly rendered him unconscious. In 1963, against the Yankees in the World Series, Howard smote a liner that shortstop Tony Kubek leaped to catch. Then the ball, in defiance of physics, kept accelerating and even rising until it reached the left-field pavilion.

The 5-foot-5 Freddie Patek leads off while Frank Howard plays first base.

In that Series, Howard slammed a 461-foot double in Yankee Stadium that reached the monuments in left-center. Because the Dodgers were always in pennant races and depended on speed and contact hitting, Howard became superfluous. He wanted a trade and Buzzie Bavasi obliged him with a whopper. To get lefthander Claude Osteen, Bavasi gave the Senators Howard along with starting pitchers Pete Richert and Phil Ortega, third baseman Ken McMullen and first baseman Dick Nen. The Senators didn’t build a winner out of that package but certainly got an attraction, and Osteen saved the Dodgers in 1965 and 1966.

But off the field, Howard was in step with everyday life to an unusual extent for a major league star. He cajoled his teammates to spend a few minutes after games with fans. “As Pee Wee Reese said, the day they don’t want your autographs is a sign you’re in trouble,” Howard said. Scrapbooks throughout America are filled with photos of Howard smiling from on high.

Not to trespass on this column, but I can attest to this. On July 9, 1965 I attended my first major league game. It was at D.C. Stadium between the Senators and Boston. Richert and Bill Monbouquette were the starting pitchers and Willie Kirkland won it for Washington with a base hit in the ninth. See, it didn’t really leave much of an impression on me.

Toting a Kodak Instamatic before the game, I saw Frank standing near the dugout. I asked him if I could take his photo and he said, “Why, sure,” and stood there and smiled. He only became my hero for life after that, although he pshawed in embarrassment when I mentioned it to him decades later.

He did that for another kid one time and said, “Now you can start your Rookie of the Year collection.”

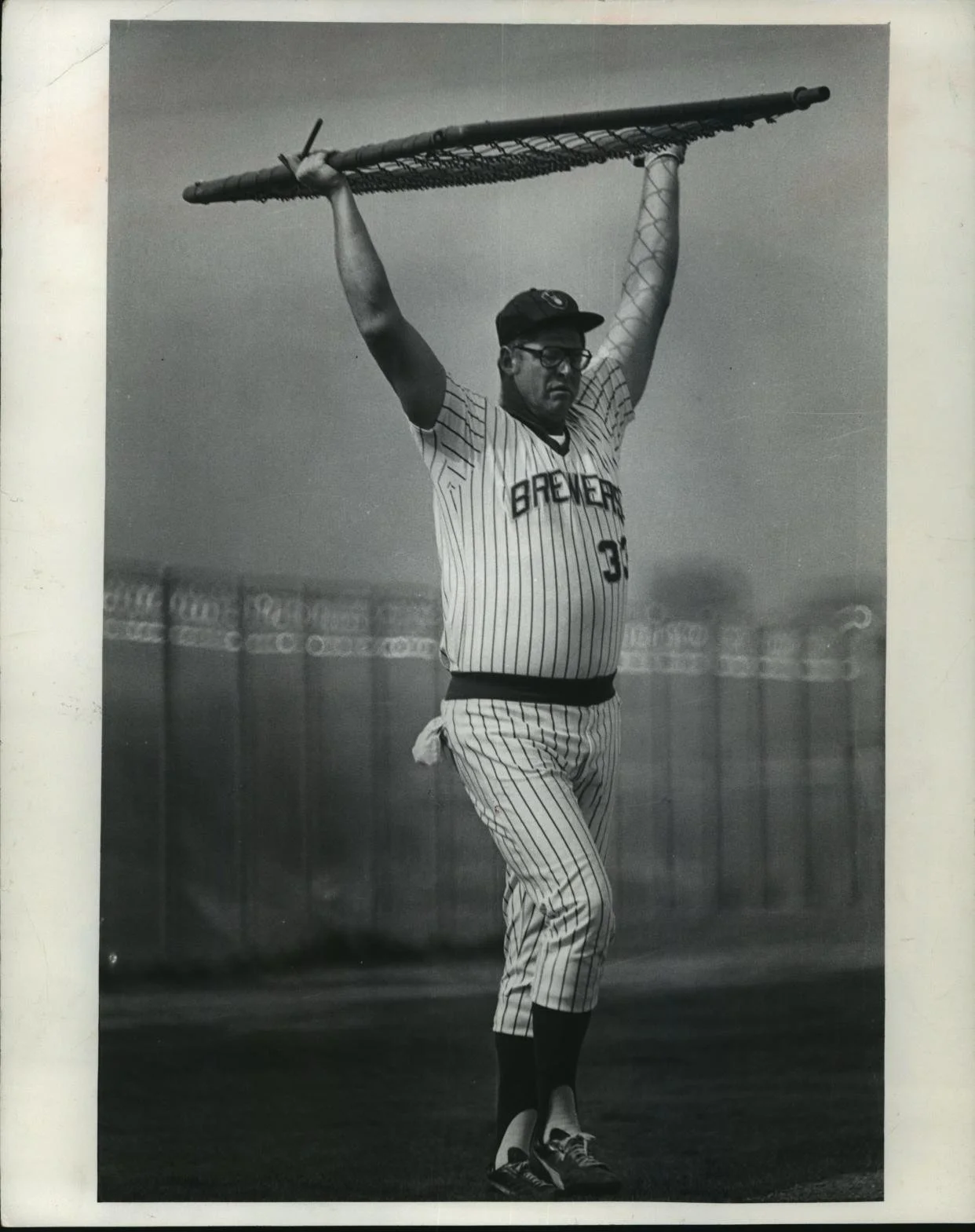

Howard coached under manager George Bamberger with the New York Mets and the Milwaukee Brewers.

Howard was on the coaching staff of the Mets and the Yankees. One day, Mets manager George Bamberger took a skeleton crew on a road exhibition game. Most of the regulars begged off. They didn’t know Howard would be running the workout in St. Petersburg that day, and that he would have them working on outfield drills for hours in the Florida sun.

“We’re going to fly-ball them to death,” he said. Next time there was a road exhibition game, everybody went.

Howard’s appetites were Bunyanesque, too. One morning he ordered six eggs, eight pancakes, and four English muffins along with bacon and home fries. Then he turned to his companion and said, “What’ll you have?” A case of beer had a very low life expectancy if it found itself within Howard’s reach.

And Sam McDowell? He’s 81 and still with us. When he read Monday’s obit his heart probably sank, along with all of ours. But now he only needs one glove.