Whicker: Fernandomania lives on in sold-out plays in Los Angeles

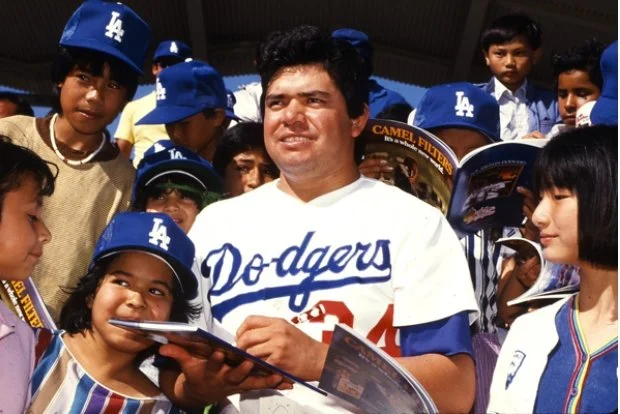

Fernando Valenzuela was - and still is - much more than just an ace Dodgers left-hander in Los Angeles. Photo: SABR

September 17, 2025

By Mark Whicker

Canadian Baseball Network

The year before Fernando Valenzuela was born, authorities in Los Angeles began clearing his stage.

It was ugly and arbitrary, with cops breaking into the houses of the 20 or so families that still lived in Chavez Ravine, throwing them out onto Sunset Boulevard. Those houses were sacrificed for Dodger Stadium, which was finished in 1962 and, today, is a place where nearly four million fans visit per year, despite the $50 parking and the $14 beers.

The last to go were the Arechigas. When their house was demolished, they slept among the ruins. They left in 1959, just a few months before the workers started on the ballpark, which Walter O’Malley had envisioned when he’d taken a helicopter over downtown. The Dodgers would prefer to leave this out of their scrapbook, and it’s not like they’re the ones who had the idea of barging into the area and evicting everyone. Developers had bullied most of the residents out of the ravine years before. But the Dodgers, compliant or not, were the beneficiaries of the final destruction of a thriving neighborhood.

Twenty years later Valenzuela arrived, and in 1981 he was an instant rock star of a dimension that baseball has not seen since. In some ways he still is. The Casa0101 Theater is in the midst of Boyle Heights, the heartbeat of Mexican Los Angeles, and it is presenting “Fernandomania,” a series of twelve ten-minute plays, one of which was written by Valenzuela’s daughter Maria. Full theaters are a rarity these days, no matter how small, but the entire run is sold out. People show up in Valenzuela jerseys, people who couldn’t have remembered the days when Valenzuela turned Dodger Stadium into what Vin Scully called a “religious experience.” He died last October at 63, eight days before the Dodgers beat the Yankees in the World Series, the same way they did in Valenzuela’s rookie year.

One reviewer who apparently couldn’t grasp the name of this production complained that Valenzuela himself was a part of only three of the plays. But it was about the community, not just a pitcher. And it resounds because almost half of the Dodgers fan base is Latino these days. That can be precisely traced to Valenzuela and Jaime Jarrin, the Ecuadorian who, like Scully, is honoured at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Few Dodger games were televised then, so Valenzuela’s fans listened to Jarrin on the radio. Then Jarrin would interpret Valenzuela’s observations in the press conferences, since Valenzuela, to the end of his career and well after he was a fluent English speaker, always spoke Spanish in public, Eventually he would sit next to Jarrin in the booth.

These were “Doyer” fans, because that’s how you pronounced it if you were learning the language. It’s not contemptuous at all. You see “Los Doyers” T-shirts at the Stadium today. For them, Valenzuela’s arrival was a blessed event, an unforeseen payback for the evictions, a license to feel at home.

“He made us proud to be Mexican,” said more than one character in these plays.

And yet Fernando and the Dodgers seemed so far away.

“I took four buses,” says Victor, who actually did get to a game.

Daniel is a young Dodger fanatic who schemes to miss school on the day the Dodgers are in Montreal for Game 5 (of a best-of-5 National League playoff). His dad puts his foot down, but all is well at the end — the teacher brought in the TVs, and all the kids saw Valenzuela pitch the Dodgers into position on a frigid afternoon. When he was removed from the game, he smiled and pretended he was smoking a cigarette, as the vapor came through his fingers. Shortly afterward, Rick Monday slammed what stood as the L.A. Dodgers’ most famous home run, at least for seven years.

Valenzuela put the same spell on the Dodgers’ Anglo fans, of course but only because of his unorthodoxy. He was stout, and his eyes drifted to the sky as he wound up, and he threw a screwball, and he could also hit. He also had the serenity of a great musician, hearing and sensing things that only he could.

In East L.A. Valenzuela could have been a brother or a cousin, but what they admired was his fight. The Dodgers trailed the Yankees 2-0 in that ‘81 Series, and Valenzuela was not at his peak in Game 3. He gave up nine hits and walked seven. He also stayed in there, and the Dodgers won, 5-4, and so what if it took 147 pitches? Nobody was counting anything but the score back then.

Valenzuela has rarely been considered a Hall of Fame candidate. He won only 173 games and was 20 games over .500. His ERA (3.54) and his career WHIP (1.315) are pedestrian. Burned out, he kept pitching until he was 36 and his numbers suffered. But for six years he was dominant. He finished first, second, third and fifth in Cy Young voting, and he pitched at least 251 innings per season from 1982 through 1987. He led the league three times in complete games, 20 of them in 1986.

His early career can’t compare with the way Sandy Koufax finished up, as if anything ever could, but Koufax sailed into Cooperstown with 165 total wins. At some point the numbers need to be separated from a player’s contribution to the game, as to his impact on his city. Put it this way: It’s doubtful that theaters will be staging Mike Mussina retrospectives.

At one point in “Fernandomania,” a character ends a scene with, “And, you know, the Dodgers would never let down their fans,” which brought some tense giggles from the seats. The Dodgers did deny access to ICE agents who wanted to stage their operations at the Stadium, but have been relatively silent on the raids that have disrupted the lives of nearly all Latinos in the city. Then they pledged $1 million, total, to 1,000 affected families. That’s not nothing, but it also seems like couch change when measured against the club’s $1 billion revenue in 2024.

So there was a wistfulness to “Fernandomania,” a nod to the power of one kid who came from nothing and brought everything, a time that will not be duplicated. You needed to be there, on those maniacal nights. One night on a stage in Boyle Heights is the next best thing.