Whicker: Underrated Lolich was Tigers’ workhorse and World Series hero

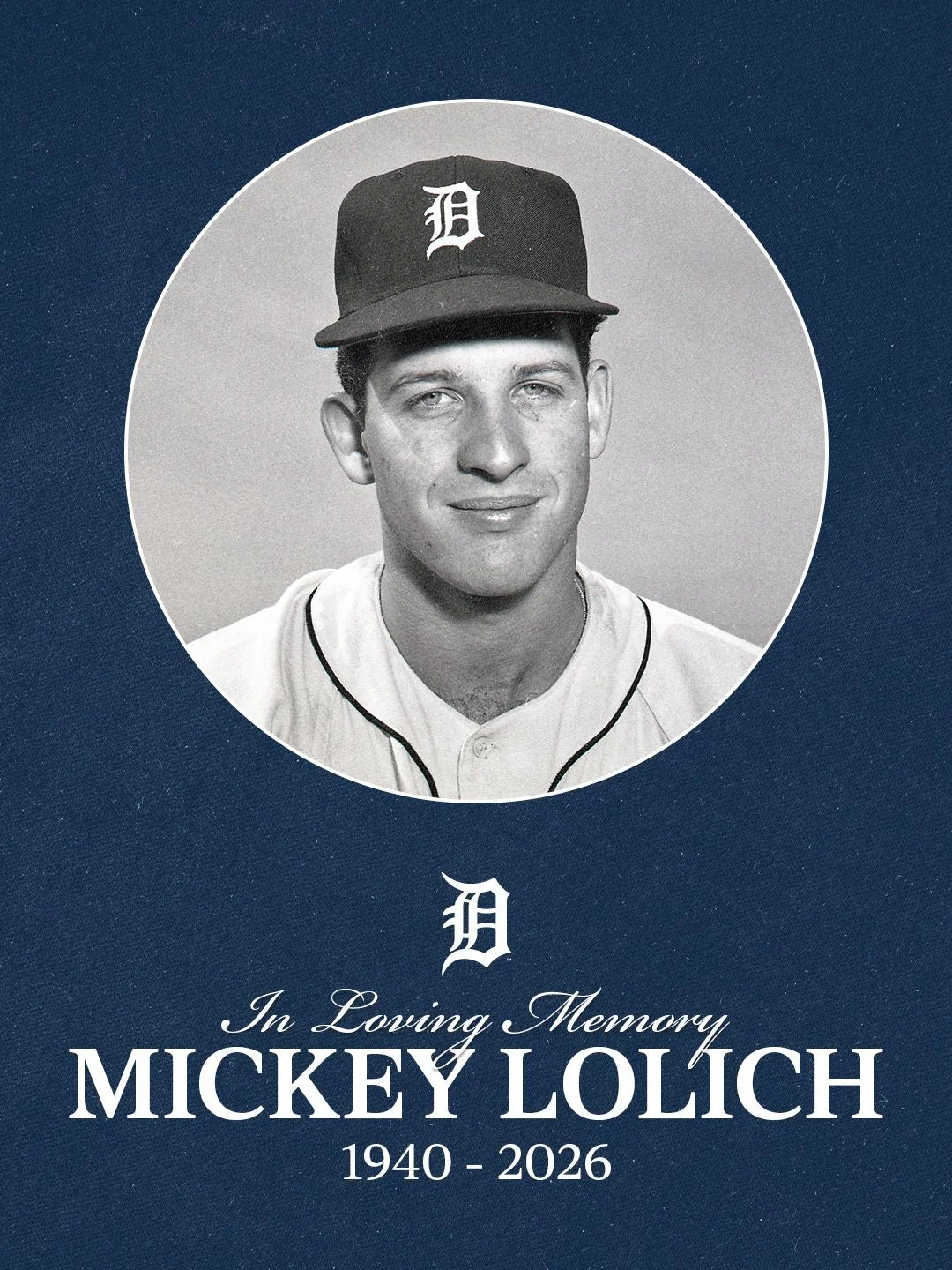

Former Detroit Tigers ace Mickey Lolich died on Wednesday at the age of 85. Photo: Detroit Tigers

February 6, 2026

By Mark Whicker

Canadian Baseball Network

Of all the crusaders who purport to Save The Pitcher, no one has suggested hot water.

No one would dare. If a pitcher went to the shower and turned the H knob to the boiling point and absorbed it for 30 minutes, his next game might be in Peoria. Ice, not heat. That’s how you do it.

Actually, one guy did perform the arm boil throughout his career. He only pitched 3,638 innings in his 16-year career, and he only completed 195 of his 496 starts.

“I did it my whole career and I never had an arm problem,” Mickey Lolich said.

But then Lolich rode his motorcycle to the ballpark in Detroit, and his body was built for a bowling league, and he didn’t like to run in between starts because he suffered from a rare malady.

“I’m short-winded,” he said.

One sportswriter said Lolich pitched left-handed, wrote right-handed and thought sideways. The fact that he didn’t take himself seriously became contagious. He was an afterthought for much of his career, the understudy to Denny McLain, who won 31 games in 1968. Then the World Series came around, and Lolich made sure no one ever forgot him again.

He is the last pitcher to win three complete games in the same Series, and in Game 7 he beat the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson to bring Detroit back from the dreaded 3-to-1 hole. He died Wednesday outside Detroit, far from his native Portland, where he was the ballboy for the minor league team and where he had retreated because he didn’t like Detroit’s double-A manager. Lolich was 85, and he lived long enough to see complete games being pitched in a World Series again.

The ‘68 Tigers were a classic collection. McLain played the organ. Norm Cash was a rogue who once took a table leg to the plate against Nolan Ryan, telling umpire Ron Luciano that it would work about as well as a bat. Willie Horton, who’d gone to Northwestern High in Detroit, led the club with 36 home runs and was an epic outfielder thrower, as well as an all-purpose brawler. Gates Brown, the ace pinch hitter, was imprisoned at the Ohio State Reformatory. He hit so many balls over the wall that prison officials brought in major league scouts, and Brown was paroled early to play for the Tigers.

There was Pat “The Dobber” Dobson, who once campaigned for a pitching-coach position by saying, “Who knows more about pitching than me? Look at the crap I’m getting away with out there.” There was Eddie Mathews, the Hall of Fame slugger, wrapping up his own colorful career. And there was manager Mayo Smith, who picked the World Series as the perfect time to introduce centre fielder Mickey Stanley to shortstop. Stanley had never played shortstop before, but Smith preferred him to incumbent Roy Oyler who had gone “0-for-August.” This way Smith could get Al Kaline, Mr. Tiger, back into the lineup after he’d been injured. Against the Cardinals, Kaline hit .379. St. Louis was the defending champion and had a lineup full of incipient baseball and broadcast legends. Gibson kicked it off by striking out 17 Tigers, a World Series record. But Lolich responded with a six-hit win in Game 2 and also hit a home run off Nelson Briles. At no time in his minor or major league career did Lolich hit another homer.

“I’ve always been the guy I wanted to pitch to,” he said.

The Cardinals won Game 3 and 4 in Detroit. Then Lolich gave up three runs in the first inning of Game 5. The Cardinals didn’t score again, and Horton threw out Lou Brock at the plate to stop a rally. Brock later said he didn’t slide because no one had thrown him out all year. Kaline got the key hit in the 5-3 win.

Detroit and McLain routed St. Louis, 10-1, in Game 6. That set up Gibson vs. Lolich for the whole pot. Smith told the Tigers beforehand that Gibson wasn’t Superman.

“Then how come I saw him changing clothes in a phone booth?” Cash asked.

But Everyman matched Superman for six scoreless innings. In the seventh, Curt Flood botched Jim Northrup’s drive to centre, scoring two Tigers. Lolich took it from there and won, 4-1.

That Series ignited Lolich’s career. In 1971, he was 25-14 with a 2.92 ERA, started 45 games, completed 29, threw 376 innings and struck out 308. Yeah, 376 innings. This year’s innings leader in the American League was Boston’s Garrett Crochet, with 205 1/3.

In 1972, Lolich was better, going 22-14 and 2.50, with a 1.088 WHIP. Lolich topped 300 innings in four consecutive seasons, and he rarely left it up to the bullpen. In 1971, when he unaccountably lost the Cy Young Award to Vida Blue, Lolich averaged 8.4 innings per start.

“He had the greatest arm I’ve ever seen in my life,” McLain said when informed on Lolich’s death. “He could tell the hitters what was coming and they couldn’t hit it.”

In Portland, veteran pitcher Gerry Staley had taught young Lolich how to make the ball sink. In 1971, Lolich picked up a cut fastball. That, and a curve, was all he needed.

“I tried to throw two of my first three pitches for strikes — here, hit it,” he said.

He ended his career as the top strikeout left-hander in American League history, with 2,832 and it would be 44 years before CC Sabathia would surpass that. Counting the 1972 ALCS loss to Oakland, Lolich was 3-1 with a 1.67 ERA in postseason. He never got more than 30 percent of the votes in any Hall of Fame election, probably because his career record was 217-192, but in 1975 the Tigers gave him 14 runs in 14 consecutive starts, and he went 1-13 in that stretch.

The next year Detroit traded him to the Mets, who blinked when they saw Lolich putting his arm in a watery volcano. They suggested ice. Lolich suggested something else. Hey, it’s the Mets. Lolich had a 3.22 ERA that year, but retired soon afterward, running a successful chain of doughnut shops, which seemed appropriate.

“Pure muscle,” Lolich would call his love handles.

The only real conflict Lolich had, in his Detroit years, was serious enough. Riots tore apart the city in 1967, and Lolich was a National Guardsman. He was activated during the season, missing two starts, but toting a rifle and guarding radio towers. When he came back to the Tigers he was notified that activist groups had threatened to assassinate him during the game.

Cash came over from first base, just before the first pitch, and said, “This is the last time you’ll see me tonight. It’s easier to shoot two than one.”

He refused to visit Lolich until game’s end.

In recent years, Lolich’s memory has benefited from a pitching descendant. Tarik Skubal has won the last two Cy Young Awards in the American League. He is left-handed, he wears No. 29 as Lolich did, and he’s a stocky fellow. Older Tigers fans see a little bit of Lolich on him, but the city suspects it has to embrace Skubal as hard as possible because he’ll become a Dodger or a Yankee when his turn at the truly big money comes up, if not before.

Skubal went to arbitration this winter and won. The prize was $32 million, an all-time record. But Skubal still can become a free agent at the end of 2026, and it seems even more likely now, because the Tigers also signed Houston’s Framber Valdez at the jolting price of $115 million over three years. That includes a $20 million signing bonus and gives Valdez an opt-out after 2027.

(I haven’t heard anyone say the Tigers are ruining baseball. Have you?)

Valdez was 13-11 last year with a 1.245 WHIP, his worst since 2021. He isn’t even a knock-off facsimile of Skubal. He’s also three years older, at 32. Skubal is 31-10 the last two seasons with two league ERA titles, and for his career he’s averaged 10 strikeouts and two walks per nine innings.

Obviously Valdez is Skubal-insurance, but the two can give the Tigers an October-worthy rotation. And, just as obviously, this will be their most pressurized season in a long while. Too bad Lolich won’t be around, to get them comfortable with hot water.